I have asked this question of many people around me recently. I received a whole range of answers none of which were right or wrong. For me, inspiration is very subjective and extremely individual. What inspires me, may not inspire others. Inspiration is important for me to fuel my desire and drive to be a better person and achieve my goals.

There are many things that inspire me. In this day and age where “fame” often equates to “infamy” – high profile people rarely inspire me. It is, more often than not, ordinary everyday people that inspire me.

Recently, I met a group of parents of children with cancer. These were parents who were working hard to build a life for their families and then were struck by the unthinkable – their child was diagnosed with cancer. They craved “normality” – kids growing up, doing sport, making friends, making them laugh or cry and doing what kids do. What these families were thrust into was a maelstrom of pain, agony and chronic health issues for their little person. These parents had to fight with ferocity that they didn’t know they had to keep their collective heads above water. These “ordinary” parents were anything but ordinary and I felt incredibly privileged to have met them. It gave me even more determination to achieve my goals to make a difference.

There are many others in my life (including my dog!) who have shown similar determination, strength, dignity and fortitude. They are people (or animals) that I think of when the going gets tough, when I am despondent for any reason or when I am hurting physically and mentally.

My inspiration is all about my “why”. Simon Sinek asked the famous question “what is your why?”. His argument was that those companies and individuals who were driven by their “why” ultimately achieved or exceeded their goals.

My “why” is that I want to make a positive difference to people’s lives. When I meet or hear of people who are striving (with dignity and grace) for positive change for others or themselves……this inspires me greatly.

I am coming to the end of a very challenging 6 month study program on the Fundamentals of Transactions (through Influence Ecology) which has been an introduction to transacting more powerfully to achieve my goals for health, work, career and money. I have studied and worked hard at this – my business is growing, I feel healthy and well and most of all, I know what my goals are and how I can go about achieving these. Inspiration, while not necessarily scientific or evidence-based, is helping me get there.

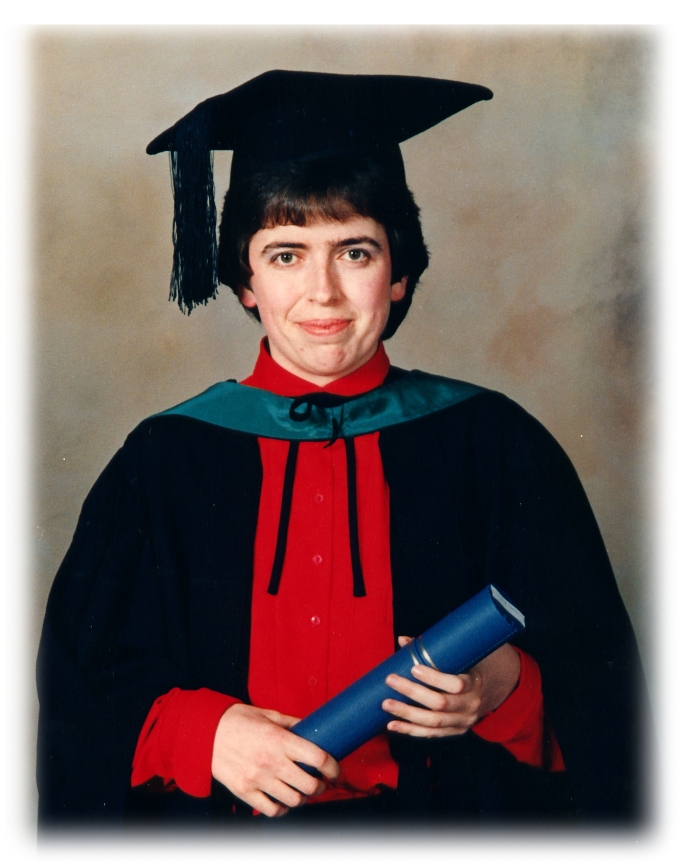

I will leave you with a quote from Abigail (in the photo), an 8 year old young lady who is in remission from brain cancer. Abby came to visit my martial arts class recently to show them how she can do push ups (on her toes) and one legged push ups (on both sides)! On the way into the class, Abby said to me “I’ve had 55 thoughts today”.

Well Abby, you might be small but your thoughts and determination inspire me!

Who inspires you?